Failing Each Other: Challengers in the Fight for Brooklyn

A Look at Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn

by Jessica Cannon

Over the past few years, I’ve had the opportunity to witness the “Battle for Brooklyn”1—a conflict waged on many fronts between developers and communities. It has been an elaborate bout through which the schisms that lie beneath the skin of the community have been exposed. These often-concealed lines have divided neighbors and made it difficult to sustain the initial cohesion that came in response to development. What exactly are the communities of Brooklyn up against? In the beginning, it was the developers, but the struggle has ended up being much closer to home.

To start at the beginning and make an extremely long story short, the communities of Brooklyn, New York, came together to fight the “Arena Plan,” an effort by developer Bruce Ratner to bring the New Jersey Nets to the borough, where they would be housed in a Frank Gehry–designed arena. Included in the proposal (but conspicuously omitted from the name “Arena Plan”) are sixteen high-rise buildings that would tower over the existing neighborhood. Three of the buildings eclipse the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, which has been the tallest building in Brooklyn for decades. To channel the spirit of Ratner’s colleague, Donald Trump: this might be the biggest, most spectacular, shiniest, most starchitectural development ever to happen to Brooklyn.

In the other corner, formed in response to Ratner’s proposal and representing the community, is Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB). DDDB’s strategies are somewhat unique in that they combine aesthetic practices with more traditional legal routes. Included in the group’s efforts are the creation of public art, the collaboration on alternative planning, the application of a cohesive graphic counter-identity, and the organization of block parties, bake sales, and formal community meetings and rallies.

Urban development often features a familiar story: developers use financial and political leverage to present their plan as the only plan, while the community becomes defined as a negating force in relation to development. DDDB has hosted several events that highlight the positive attributes of the communities affected by the Ratner proposal. The DDDB Block Party brought people together to celebrate urban street life—a way of life in Brooklyn endangered by the proposal. DDDB also took to the streets with bake sales. Through baking, an activity intimately associated with the home, participants created goods to fund an organization whose mission is to preserve the very homes they bake in. These activities confront the public with the human scale of development—something unaccounted for by the planning rhetoric, which promises to “turn an under-utilized industrial site into a vibrant, mixed-use community.”2 From the music blasting at the block party to the families stepping up with baked goods, it was clear to anyone paying attention that there is a vibrant community already in existence.

The early public art created by DDDB was aimed at raising awareness about the plan’s impact on existing communities. For one project, a slide show, projected at dusk onto the side of a contested building, depicted residents photographed in their homes—the very homes threatened by Ratner’s plan. These images brought the vulnerability of the individual in their private space to the visibility of the city street. Shortly after the slide project, planning workshops were held and the public was invited to re-envision their community. After fifteen months of debate and several proposals, two very different plans were presented to city council members as feasible alternatives to the Ratner proposal. The first plan shifted the arena to a nearby site. The second plan re-envisioned the neighborhood without an arena and featured low-rise housing similar in scale to the current architecture, along with new green space.

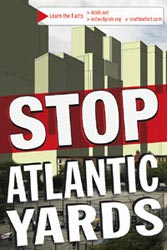

Around the same time, graphic designers became involved, creating posters, flyers, and mailings that were disseminated and displayed throughout the impacted neighborhoods. These materials soon graced apartment and shop windows and conveyed a unified opposition to Ratner’s plan. This is one example of how DDDB used design and branding to communicate, a decision that lent the group credibility within the media—especially when juxtaposed with the polished public relations of the developer’s office.

While DDDB was able to bring people together to generate ideas, they were not able to agree on much more than the flaws in Ratner’s proposal. Ratner, on the other hand, had a clear articulate vision, as well as money, political support, and a public relations team that carefully managed every move in the media. According to Daniel Goldstein, current spokesperson for DDDB and lone holdout in his large apartment complex, the media remains the most contested site in this battle. Through techniques such as design and branding, DDDB enveloped other interest groups to present itself as the oppositional authority to Ratner’s proposal. While other similar groups worked independently, most people involved identified themselves with DDDB. The media identified the group as well, and whenever a story required comment from the community, DDDB was called. As time went on, Goldstein became the media contact. The consolidation of many voices into one came at price: Goldstein took on the responsibility of delivering a consistent, polished media-ready message on behalf of a group that already consolidated their own message of community.

Encouraged adherence to the DDDB aesthetic alienated some in the community who aligned themselves with the group early on. A woman who made T-shirts for the group was discouraged by Goldstein because her shirts did not feature the proper DDDB color and logo. Looking back, this seems silly, but it was part of DDDB’s strategy to engage Ratner’s plan using the same aesthetic language. This strategy was effective in recruiting volunteers and dealing with the media. However, it is easier to display a poster than it is to attend a meeting, and the group achieved the appearance of unity at the cost of participation.

Despite their efforts, DDDB has been unable to prevent the impending Ratner development. Regardless of the outcome, though, there is much to be learned from the fight. In particular, the actions of DDDB have shed light on the elusive nature of community. It is clear that underlying the block parties and bake sales are other forces at play. A recent conversation with Joel Towers, a founder of DDDB and practicing architect and educator, shed some light on the challenges of the process: “The DDDB project unearthed a great deal of potential to develop strategies and tactics that are about community organization and agency. It also revealed in rather brutal terms the mobility associated with wealth, the fact that community is a gross term, especially in neighborhoods that are in the midst of transformation. This plan affects one of the most diverse communities. Because of this diversity you have different degrees of mobility, agency, attachment to place, and those forces, ultimately the forces of capital ended up being stronger than our ability to produce community with other kinds of kinship patterns.”

As it turned out, diversity—a factor that led many to be attached to this community—proved a great challenge in unifying its residents. Diversity is a nice word, but when it means that some people won’t be able to find adequate housing and others will, it has little if anything to do with community. The forces of capital determine the outcome, not the ideology. A challenge that highlighted this divide came when DDDB held meetings to envision Brooklyn’s future. The initial appearance of unity came from the widespread opposition to Ratner’s proposal. When DDDB took on the task of re-envisioning the possibilities, their mission became less clear and was refracted through the lens of three groups. One group recently bought into the neighborhood during Brooklyn’s real estate boom. Another group was comprised of a creative class that began inhabiting the neighborhood twenty years ago. The third and most socio-economically fragmented group represented people who lived in the neighborhood for generations, but had less mobility than their neighbors. The borders that existed within the community made it difficult to reach consensus and also made it clear that the neighborhood had begun a transformation years before Ratner’s proposal. Ultimately, the vision of Brooklyn that most residents rallied behind was a nostalgic one—wide brownstone-lined blocks with stoops onto the street. This vision of low-rise housing and green space was not a viable way to create affordable multi-family dwellings and stave off large-scale development.

From its first sensational press conference, hosted by Frank Gehry and Jay Z (one of the three-hundred Nets owners), it was clear that the developers were media savvy. DDDB did not only contend with the plan, but also with the glorious problem of people who could not easily be compressed into logos and sound bytes. Their website, developdontdestroy.org, features a blow-by-blow account of the opposition’s fight, internally and externally. Containing over three years’ worth of material, it is a great resource and educational tool that provides a context for sharing experience and developing strategies. What we learn from this and other efforts may be of some help as we continue the fight for our respective Brooklyns.

I am sincerely grateful to Joel Towers for sharing his experiences, to Laura Auricchio for her guidance, and to Daniel Goldstein for assisting with materials.

Notes

1. Tim Soter, “The War For Brooklyn,” Time Out New York 565, 27 July–2 August 2006. (back)

2. Empire State Development Corporation, “Atlantic Yards Arena and Redevelopment Project: Environmental Impact Statement,” 29 March 2006, available at www.empire.state.ny.us/pdf/AtlanticYards/ArenaFinalScope3-31-06SC.pdf: (back)

Block Party Communty Building event (click image to expand)

Supporters with campaign t-shirts and color schemes

Speaker with Campaign banner in the background

Campaign poster

All photos courtesy Daniel Goldstein