| |

|

| |

Temporary

Monuments

Lize Mogel

|

|

The fall of the World Trade Center in September was immediately

followed by a media-driven discussion about a memorial,

or a material gesture of remembrance. Certain of the media

looked to artists, architects and other "experts"

in the production of meaning to interpret the massive

loss and conflicting emotions experienced during the aftermath

of the event. The New York Times, bellwether for

the opinions of a portion of NY society, ran articles

asking certain cultural producers what they thought should

replace the physical and psychological hole left in lower

Manhattan. Several artists proposed parks; Richard Serra,

in keeping with his monumental body of work, called for

new buildings, even larger than the previous ones.

Within the art world itself, artists like many other citizens

met in groups informally and also within the confines

of institutions (museums, galleries, art schools). Galleries

and museums mounted exhibitions of work responding to

the events of 9/11; the New Museum hosted an exhibition

of artists from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Residency

Program which had been housed on the upper floors of Tower

1. One piece out of all the tributary work effectively

spoke of the demise of modernism and economic stability

symbolized by the WTC; Mahmoud Hamadani's recreation of

a 1970's Sol Lewitt modular cube structure, now crumbled

and fallen.

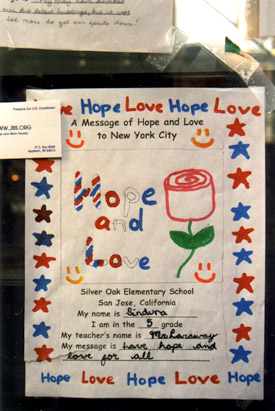

Many artists’ responses did not always enter a broader

public discourse. Instead, a new public art formed on

the street, with the vast accumulation of posters, objects,

and displays created and placed by a portion of the city’s

population; including residents, workers, tourists, and

passers-by. The public itself. This archive is, in its

totality, an inclusive, participatory artwork, which dwarfs

any deliberate gesture made by artists or institutions

to interpret the events and aftermath of 9/11.

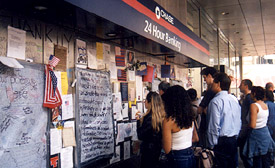

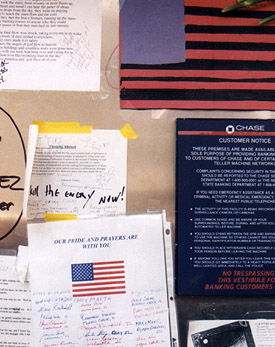

Immediately after the WTC fell, missing posters went up

all over lower Manhattan. These were functionally futile

but had great value as a larger phenomenon; a temporal

memorial to the dead, an archive of souls. The posters

were eventually taken down (although an occasional new

one appeared on downtown lampposts) and replaced by handmade

signs, photographs, t-shirts, candles, stuffed animals,

flowers (real and fake), flags, banners. These collections

or shrines were at first distributed within any significant

gathering place below 14th Street. They are

now contained in fewer areas; a church fence near Ground

Zero; the subway station at Union Square; Grand Central

Station. All critical points of convergence and divergence,

and of maximum pedestrian traffic.

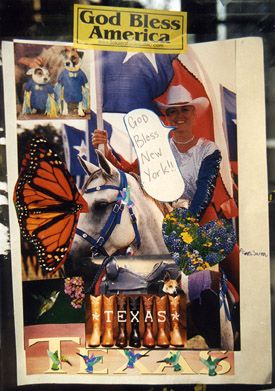

Most of the offerings near Ground Zero seem to be from

elsewhere- after all, it is a tourist site. There is a

visible effort to belong through mark-making, regardless

of the origins of the mark-maker. In the graffiti covering

the Paris cemetery where Jim Morrison is buried, the iconic

word "Jim" is carved into trees and sarcophagi, transcending

a need for translation. The repetition adds to Morrison's

mythos, whether inscribed in true mourning, idolatry,

or trendy grave-scribbling. These gestures are doubly

for the absent subject and for the author herself.

The singularity of the cemetery graffiti suggests an overarching

presence, despite subtleties of penmanship. The collection

of objects commemorating the WTC represents a more complex

authorship, stylistically and functionally diverse. Can

personal marks be writ large and monumentalized- or does

the monumentalization and reproduction of this type of

gesture remain purely sentimental, cliche, or kitschy?

This stands in opposition to traditional notions of monumentality;

size, mass, centrality, and permanence.

The New York Times championed the idea of Luxor-style,

twin searchlights shining upwards, filling the absence

left by the World Trade Towers with a brilliant ghost.

The intangibility of light is appropriate here, but the

purity of this abstract gesture is reductive. It speaks

more of the loss of architectural space than of bodies.

The physicality of the WTC is absent (wallboard, hallways,

cubicles, sweat and smell of human habitation), perhaps

better symbolized by the unruly shrines left as offerings

rather than the grand narratives of hope, goodness and

redemption symbolized by the columns of light. These collections,

or temporary monuments, to the WTC present a new paradigm

that cannot be easily contained within an institutional

frame.

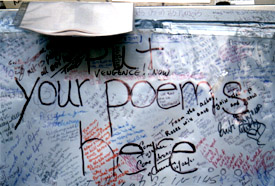

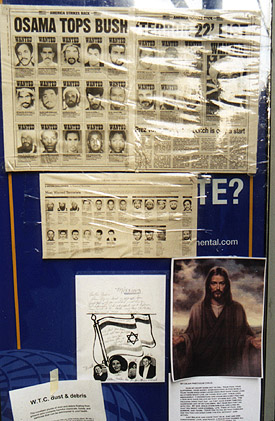

There is an absence within this public artwork: that of

dissent. The mutable arrangement of objects exists within

social space that is legislated as such, by unspoken rules

of conduct that rooted and temporary communities perform

daily. During the first week after the attacks, an abundance

of hand-lettered signs appeared, expressing political

viewpoints and annotated by anonymous others. A month

later, with free speech rights vastly curtailed, all evidence

of true public discourse was removed in favor of sympathetic

and patriotic statements. Is this unity or a civic editorial

process? It remains to be seen if any future memorializing

gesture can reflect the true range of viewpoints. The

enormous absence of the WTC towers suggests an enormous

presence, which can be replaced by another monolith or

by a deliberate massing of the polysemic and the personal. | | |

|

home | bios

| about |

contact

| links

©

2002, The Journal of Aesthetics and Protest

|

|