|

||

i love to we SF Christina: SF Victory Gardens 2008 taps into several current and historical movements of participatory urban agriculture, can you talk about your relation to the SF community garden culture? Amy: I have no direct connection to the community garden culture in SF. My relation to agriculture stems from my parent’s farming practices. My father was an industrial farmer in the San Joaquin Valley and owned a pesticide company and my mother was an organic farmer and activist near San Luis Obispo. Although their ideologies were seriously opposed, my parent’s involvement in growing food was politicized in their own way; my father heavily involved in water politics and labor issues and my mother fighting local strawberry farmers to stop using Malathion. Through canvassing and attending public hearings I was introduced to food politics in action. My interest in urban agriculture evolved through a desire for aspects of the rural, but not being ready to be away from the urban environment. In 1995, my best friend worked for the now-defunct San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners. (1) SLUG had always been in my mind as a successful, municipal project. It had many simple frameworks for cultivating citizen action and collective ownership of neighborhood programs. For example, if ten people in a neighborhood got together and approached SLUG, they would organize a workday and build a community garden for the neighborhood. The process of rallying neighbors took advantage of an organizational network that was already established and it strengthened neighborhood relationships. Currently the Victory Garden program has teamed up with Slow Food Nation to plant a garden in front of City Hall. The Victory Garden program runs through the Garden for the Environment and a network of volunteers. The garden at City Hall will create a community for urban gardeners. Each major urban agriculture organization will have a plot to demonstrate their growing techniques. This garden will shed light on the diversity of garden practice and groups in the city; City Slikcers, Alemany Farms, Edible Schoolyard, Garden for the Environment, and Quesada Gardens. The City sees this garden as an important symbol of their long-term commitment to urban agriculture; which includes funding, access to land and integration into public programs, schools, libraries, and parks. The city used to fund SLUG, but since SLUG collapsed, there has not been another program in place. When we went to the city to present Victory Gardens, they were extremely receptive and saw our project as a resurrection of SLUG and a promise of a program that would benefit a diverse population through education, support and employment opportunities.

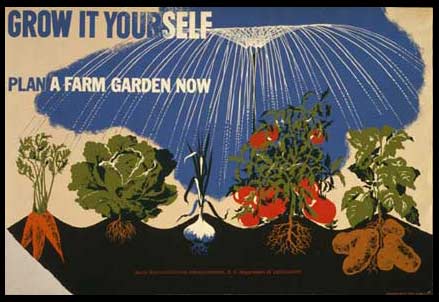

Working on a greater, municipal scale seems to be a crucial component of the project. Why was it important to you to get the city involved? My desire to work with the city was inspired by a myriad of things: time spent living in Gent Belgium over the last five years (2); the 2003 mayoral campaign in San Francisco for former President of the Board of Supervisors and Green Party member Matt Gonzalez; my general dissatisfaction with politics in this country; reading about the scale and participation of the WWI Liberty Gardens and WWII Victory Gardens. I first became aware of the WWII Victory Garden program in Laura Lawson's City Bountiful: A History of Community Gardening in America. The program was initiated in 1941 by the Office of Civilian Defense in cooperation with the Department of Agriculture. During a national garden conference a guide for the Victory Garden Program was produced and distributed to cities across the country. Between 1941 and 1943 there were 20 million Victory Gardens and 41% of our total food was being produced in Victory Gardens. The image of 20 million gardens being planted within 2 years gave me the fuel to imagine a new program with a focus on contemporary food issues. My intentions were set to revive not only a city-supported gardening program, but a personal revival to get politicized and radicalized about the current food crisis. Our food is controlled by profit-driven corporations like Monsanto. The current Farm Bill promotes production of food not fit for human consumption, and destructive farming practices that deplete soil and air through overuse of pesticides, Nearly 70% of farm subsidies go to the top 10% of the country’s biggest growers. This form of corporate welfare encourages the ongoing consolidation of farming and food into fewer hands. I might be naive, but I hope that food can be produced by a smaller network of familiar faces like “neighbors”. Since more and more businesses and corporations control "public policy", they do have the power and autonomy to develop sustainable systems and products. The homogenizing effect of power being controlled by fewer voices has resulted in the loss of decentralized decision-making made at a local level. But despite our conservative tendencies at the national level, San Francisco has been successful in moving the progressive movement forward on many fronts. It inspired me to think of the city as a place where progressive ideas can take root. San Francisco is ready for a decentralized and systemic approach to urban agriculture. To be honest I did not even know what that meant when I went to the city, but I knew that I had the historical precedent of the massive participation in the Victory Garden program and a simple proposition for the city. When I approached the city with the help of Matt Gonzalez, I was met with overwhelming interest and support. After one small presentation to the city with images and information about the historical program, namely the photo of the demonstration garden in front of city hall, 12 different city offices were ready to support the program in any way.

Within 3 months time, we had 5 city offices in support of our project, a 60,000 dollars development grant and now a garden being planted in front of city hall. Our project is a pilot project funded by the City of San Francisco to support the transition of backyard, front yard, window-boxes, rooftops, and unused land into areas of organic food production. In 2008 we will choose 15 households that represent the diversity of San Francisco to participate in the program. People can participate regardless of income, ethnicity, available space, neighborhood or gardening experience. Participants work with the Victory Gardens team to install a garden in their outdoor space and participate in two training courses at one of the Victory Garden teaching sites. When you talk about scale, I understand why you would want to build on a campaign that has proven to be effective in the past. But what do you make of the program’s inherent nationalism and militarism? Look at the actual campaign slogans: “Our Food is Fighting”, “Life on the Home Front”, “Join the Army of Food producers”— citizens were literally recruited as garden soldiers. What drew you to the Victory Garden program, rather than the community garden movement for example that has been equally productive since the 1970s? I do agree that there are problems inherent in the name. I purposefully wanted to keep this name to bring up the problematics of the historical context as it relates to a not so different ethos of today. That said, I wanted to use this as an opportunity to explore the notion of reclamation and redefining of an idea or program. Conceptually, it echoes my conviction that we cannot keep thinking in terms of "new" ideas. We need to look to past models and build upon them – adopt relevant concerns; conservation, education, land use, urban agriculture and nutrition etc. and apply them to our current political reality. Yes, the WWII V.G. program, was accompanied by a slurry of propaganda: "Join the Land Army"; "Every Garden a Munitions Plant"; "Dig for Victory", etc. These slogans prompted Americans to take part in a war remotely through food--to become engaged in the soil or the homeland turf. "Victory" for the WWII Victory Garden program was “winning the war.” Winning the war by growing more food at home so that the nation could send more food overseas to support the war effort. What do we want to be cultivating as urban farmers today? "Victory" for the Victory Garden 2008 program is independence from a food system whose values we do not support. “Victory” for the Victory Garden program is reducing the food miles associated with the average American meal by growing more food locally. “Victory” is building an alternative to the American industrial food system which we view as injurious to ourselves and to the planet. In this way we redefine Victory within the pressing context of urban sustainability, while building upon the previously successful Victory Garden model. I had my reservations about keeping the name Victory Gardens, but it is something that people across a wide spectrum understand. If we are going to truly cultivate a large-scale food revolution it must be popular. The name gives us a chance to discuss gardening in a time of war. Or perhaps also an opportunity to discuss the reasons for the war on Iraq? Yes. The problematics of the title opens up space for conversation, like this one! If it were called "Happy Gardens" like one city official proposed, maybe we would be denying ourselves from looking at some of the darker realities associated with national and international food policy. Look at the new laws imposed on Iraqis denying their right to food sovereignty and developing an independence on multinational corporations. One of the hundred laws drafted by Paul Bremmer III’s Coalition Provisional Authority was the Plant Variety Protection provision. This prohibits farmers from re-using seeds of protected varieties or any other variety listed on their long lists. On top of this, the national seed bank in Abu Ghraib was looted as a result of U.S. occupation in Iraq. Shortly after, American soldiers began distributing over four hundred and fifty tons of grain seed to farmers in Iraq through a program called “Operation Amber Waves”, implying that the following year these farmers will have to buy seed from the maker’s of this seed… Monsanto. Along with the seeds deliveries (there is an amazing photo on the U.S. Department of Defense website (3)) were color Xeroxed posters instructing farmers NOT to feed the grains to livestock.

What do you think the advantages are of turning city farming into an art project? It was an art project inspired by a national program that has now turned into a city project. The advantages of it beginning in the art museum had to do with being able to create a small-scale program to present to the city. The presentation of this project in a museum context made me focus on the aesthetics of the original program to reconsider it. A strong visual campaign accompanied the WWII Victory Program, thus I felt it important to create a series of visual icons that represented what a new urban agriculture program could be; Pogostick Shovel, Bikebarrow and a graphic campaign to be carried throughout all printed matter. [ ]

| ||