Sarah Ross is a co-founder of the Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project (PNAP). PNAP is a grassroots project offering arts and humanities classes in Stateville Prison, a maximum security prison near Joliet, Illinois about 35 miles southwest of Chicago. Work developed in classes is then exhibited in Chicago area galleries and neighborhood spaces alongside events and discussions about mass criminalization, education, art and incarceration. Sarah has almost a decade of experience working with incarcerated people and has taught art and art history at various prisons in Illinois.

HEATH SCHULTZ: I thought it would be a good place to start if you could talk a little about your history of working with incarcerated men? Why do you think this work is politically important?

SARAH ROSS: I’ve been teaching in state prisons for almost a decade now. I first started working with incarcerated women in 2001. Between my stints in art school I worked with survivors of domestic violence through a non-profit in Portland, Oregon. I started going to a county jail to talk with women about safety plans and what they would do when they got out. Four years later when I moved to Illinois and was looking for a job with my newly minted MFA and I saw a posting with a community college to teach art history in a prison; I figured — I can do that! But I was pretty naive.

Jail and prison are totally different as are the populations of men vs. women. At first I thought I could bridge the divides between differences (free, unfree, class, race, gender), or better “education” would be a bridge of those divides. But I quickly realized, in a prison, I could not shake this profound power I had of being able to move where you wanted, when you wanted. Going into a prison as a free person reiterates the level of inequalities between freedom and confinement. They are stark, brutal and tragic. It made me uncomfortable to be in my own skin there, to have that much privilege, to witness this catastrophe of confinement and only have the tool of art history to wield. Within six months I thought I couldn’t do it. I stuck it out and over the next few years I self-educated by reading everything I could and trying to connect with others in this movement. Between that and having really important conversations in class about race, representation, the power of images and the beauty of images, etc. is what kept me coming back.

Two or three semesters later, Brett Bloom (of Temporary Services) and I started a reading and screening group in Urbana, Illinois to collectively understand more of the U.S. carceral history. We met twice a month and the group was called Prison Impact. It was the saddest, most depressing group because not many people participated, but significantly, the subject matter was and is still angering and devastating. We met for about 8-12 months and learned a lot but ended it and about a year later we started holding the group at the prison in Danville, Illinois (about three hours south of Chicago) with incarcerated people.

I didn’t seek out prisons to start teaching… instead, I really dumbly of fell into it. Which is to say a lot about my own social position and how something like a prison figures into my daily way of living. I think prison is a kind of ground zero for the most massive inequalities in our society and therefore it must be engaged and questioned. Precisely because prisons are often isolated it is possible for many of us to not consider conditions of confinement. This is not happenstance, it is completely by design. In this way I think it’s critical to think about how spatial arrangements facilitate a kind of blindness or at the very least a disconnectedness.

HS: Do you see this design of segregation part of the privatization and new rapid construction of prison over the last couple of decades, or was it structured into the foundations of prisons in the U.S.?

SR: There are interesting analyses in architectural history illustrating how prison design has changed according to the carceral logic of the time. Prisons built in 1920 look quite different than ones built in the 1980s. Where prisons are built is another aspect of segregation — this is critical because it impacts the ability families or friends who visit people in prison and even resources (like colleges and anti-violence organizations, prison watch-dogs, etc.) to work with incarcerated people. Prisons in the early part of the last century were mostly built close to cities. This changed in the 1980s with the boom of construction and prisons went up further from cities.

The construction and operation of private prisons is important but on the whole it is a smaller part of the larger problem — the segregation and confinement of segments of the population. In Illinois the legislature passed a law that no prisons can be operated by private companies (although many of the services to prisons such as healthcare, food, etc. are private). Private or not, prisons are always funded by public tax dollars. Despite Illinois’ ban on private prison construction, it continues to incarcerate. Lots of researchers say the boom started in the late 70’s, other researchers say that every time there are major social shifts in power (end of slavery, civil rights, etc) incarceration is a feature of maintaining power.

There are also books, like The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, that illustrate a kind of ‘death by a thousand cuts’ syndrome that is pervasive throughout the system. Alexander looks extensively at case law, administrative rules, etc. that ensnare people in the criminal-legal system in new ways. A read of this and many other publications unpack how, from settlement of the nation to today, what constitutes a crime or that the definition of crime shifts to compliment the preservation of power and resources. So the criminal/crime is flexible category to enforce isolation and segregation.

HS: Could you talk a little about some of the other programs you’ve done with incarcerated people leading up to your work with the Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project?

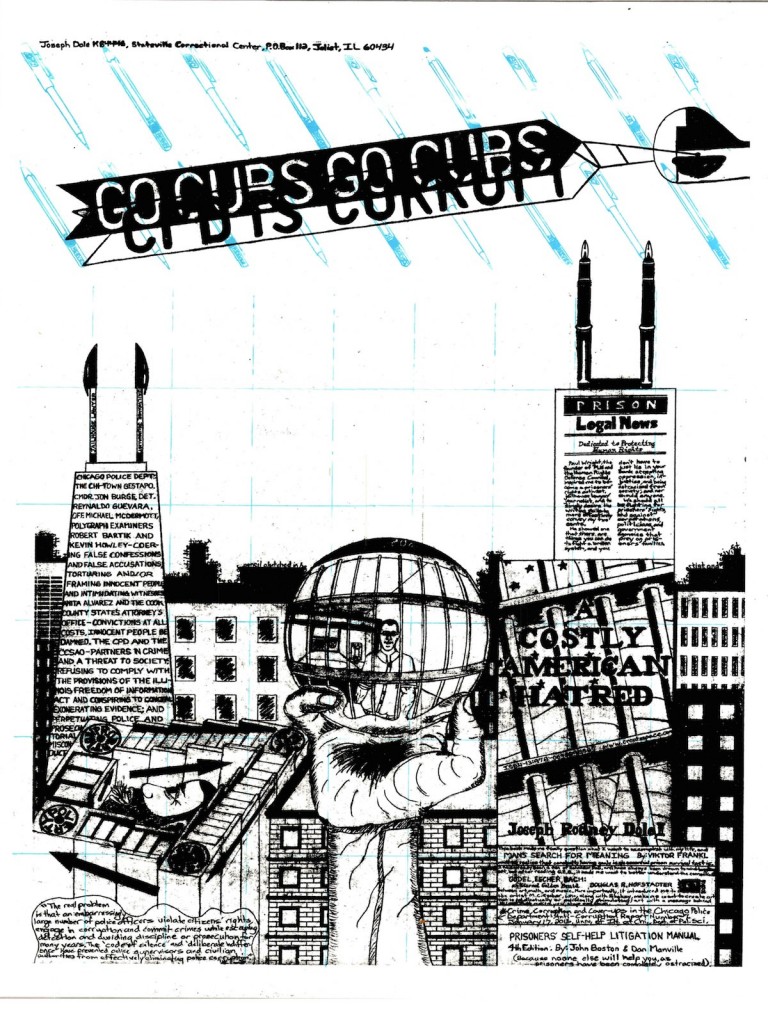

SR: Once I started teaching at the prison in central Illinois I realized I needed books for the students to write papers but there were none! I found out that the state legislature stopped funding circulation of books in Illinois state prisons in the early 2000s, so prisons had been relying on donations from some volunteer organizations and families. So I connected with a local books to prisoners organization that is really well run and does great work. I also worked with the dynamic Laurie Jo Reynolds, Nadya Pittendrigh, Laura Hsieh, Amy Partridge, Jerome Grand and families of incarcerated people who organized the Tamms Year Ten Campaign — to shut down Tamms Supermax prison.[1] I also work with a group called Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM) — a group of lawyers, artists, scholars, survivors of torture and community activists.[2] I joined about four years ago but they got started around the time Jon Burge — an infamous Chicago police officer who tortured people into confessions — was sentenced to prison for perjury (he could not be tried for torture because the statute of limitations expired). Burge ran a ‘midnight crew’ and tortured some 120 African-American men and women between 1970 and 1990. Many other people have been tortured under officers trained under Burge. The CTJM group formed with the idea of making memorials around the city to reckon with this history. We had an open call for memorials and held several exhibitions. One of the memorial propositions was reparations of the victims of torture. An Ordinance was drafted by lawyers in consultation with survivors and CTJM members. It was sponsored by two Alderman and we had more than half of City Council signed on to say that there should be a hearing on it. But the Ordinance got held up in the city’s finance committee for more than a year. With the explosion of protests around the country (because of the racist police shootings of Michael Brown and so many others) and an mayoral election, there was renewed efforts on the Ordinance about a year into the ordinance languishing in committee. The context mobilized, particularly young folks, from We Charge Genocide, Project NIA, Black Youth Project and Amnesty International (all partners in this effort) to take to the streets, the subway, city council and we did series of almost weekly actions that began in January of 2015. We had marches, sing-ins, exhibition-ins, young poets wrote about Reparations, and more. (For an example of some of this work see Kuumba Lynx’s performance “Louder than a Bomb” below.)

The pressure and national context pushed the city to negotiate a deal. On May 6, city council passed the ordinance in a truncated version of what we asked for. That was disappointing in some ways but also a historic victory. This is the first time in the nation that any government unit has granted Reparations for survivors of police violence. The Reparations give financial compensation to torture; requires Chicago Public Schools to teach the cases in grades 8 and 10; offers free city college education to survivors, their families and their grandchildren; calls for a public apology; supports a memorial and creates a center for counseling for people who have survived police violence. This is an abolitionist approach that doesn’t call for more harm but demands resources and support for the survivors, families and communities terrorized by this state violence. But there is, of course, more work to be done. We want a robust center to support anyone who self reports police violence and we must raise money for this. Finally, there are people still locked up in prison who were tortured into confessions by Burge and by police officers who trained under Burge (some of which have been identified by the State’s “Torture Inquiry Relief Commission” and are our students at Stateville).

Kuumba Lux, “Louder Than a Bomb,” 2015

HS: Can you talk a little about how you see PNAP fitting into prison advocacy, reform, and/or abolition efforts in Chicago? There is also a really vibrant radical arts scene in Chicago which you’ve mentioned peripherally throughout, do you see PNAP fitting into that milieu?

SR: What connects us to other projects working in and around the criminal legal system is that we are all asking questions about state sanctioned violence, social segregation, lack of access to resources such as adequate legal representation, decent education, food, the list goes on. PNAP is an arts and education project with the goal of facilitating rigorous classes and making compelling work with incarcerated people. In this way, if education and art can be a tool for articulating this moment in history and imaging new futures, then I believe this project works alongside the many efforts to remake what justice can look like. I think everyone agrees abandoned communities, over-filled prisons, expensive penal systems, and the perpetual cycle it creates — has to end. It’s complex and hard to see past the misery it produces or even imagine interventions that could make a dent. So when forming PNAP we thought about the tools we do have — skills as teachers, artists, etc and we hope this will help do the work of remaking the system.

As far as fitting into the art scene in Chicago — this town has amazing artists and arts organizations who have expansive views of art. One of the things I have struggled with is that people assume a kind of aesthetic from incarcerated artists — an assumption similar to what one might make about ‘outsider art’. I imagine that they think the work will be unskilled or lack critical content. In fact, because prison is a really closed environment, it does have the potential to generate a common look or style as people train each other. One person who is a really keen artist teaches another, who teaches another and a style can emerge. For instance, many artists I’ve worked with inside draw from photographs and magazines, not live models or still lifes. They also learn through books that articulate a kind of ideal aesthetic. So some of what emerges is an air-brushed style — if you are drawing from magazine images indeed, one might expected a flat look. Usually, after some time, the artist will start to add other details or work faster and looser. Of the artists we teach there is amazing talent and visual style and by combining that with outside artists’ skills I think we are able to produce something fresh, critical, and engaging. People have told me that what they see from PNAP is not what they expected. I’m excited about these moments and I have to believe they have social/political and aesthetic potential!

HS: What about PNAP as part of a larger anti-racist organizing project?

SR: PNAP is a kind of boundary-crossing project that suggests one way to work against racism is to work against the spatial segregation it produces. Both faculty and students often have our/their assumptions challenged. Faculty who are activists, educators, and politically astute people, teach inside and say “wow, I didn’t know I’d have such rigorous conversations with students”… and then we check ourselves and say “why not?”. We also have students that have said “I didn’t think that you people (college faculty, artists, or whoever) would be interested in coming here to work with us”. And there are assumptions about what, say, a white woman such as myself gets out of doing this. I always tell people to think about why they want to do this work because students inside will definitely ask “why are you here?” So there is learning and challenging on both ends.

HS: Can you give us a sense of the day-to-day of PNAP?

SR: This is probably a very boring answer but also revealing about some of the struggles involved in working inside prisons. A lot of the day to day for me and a few others involves meeting with folks about the project, writing grants and thinking about partnerships with other organizations. On days we teach at the prison, it takes about an hour to get to the prison and another 30 minutes or more to get through the gates to the school building. The classes last two and a half hours and the environment is different for each class. In the art classes we move around a lot, in other classes I see everyone sitting in a circle in deep conversation. Often in the poetry classes people read their work aloud and there is a lot of clapping and so on.

The labor it takes to make this happen is quite vast. First we raise money to stipend faculty, then four to five months prior to a class starting we recruit faculty — a mix of gender, race, skill sets, etc. All of the faculty have to go through a four month clearance with the state that involves TB tests, drug tests, two sets of fingerprints, photograph, orientation, and a few other things. PNAP has its own orientation on top of that. So before a person walks into their class they’ve spent about six to ten hours getting set up with just clearance! Our classes have to be okayed by the chaplain ahead of time. We enroll students (they write essays as to why they want to be in the class), select students and put in requests for the students to be in the classes. They are then cross-checked to make sure there are no “enemies” (according to the prison) in the same class. Then we have to request ‘gate passes’ to get all of our course materials into the prison before classes start. Also before classes start we request another set of passes that let us and our teaching tools (books, etc) in the prison. Once we get there, finally, officers check the gate passes (no gate pass, no go) and we get shaken down including taking off shoes, shaking out bras, etc. All of our materials are checked at three different gates. Then we walk about 10-12 minutes to another part of the prison to the classrooms. This is actually a more efficient version of what happens for families. They often wait two to three hours and have their own load of paperwork and searches they go through.

HS: What are your strategies for amplifying the incarcerated artists’ voices? What do you see as the most valuable thing we can learn from engaging with their work?

SR: One way I have thought about amplifying the work of incarcerated artists’ voices is to blend it in with everyone else’s. Maybe this seems counter-intuitive but one way incarceration is so corrosive is that is effectively disappears people. I’ve often wondered if we regularly saw media, writing, and art from incarcerated people if that might shift our perspective. Having art exhibitions every year is one strategy to insist on a presence in the community. This year, for instance, we’ll have an exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago in January of 2016. Other ideas have been to partner free and incarcerated artists to make work together — while it can produce new aesthetics — the work also is ‘co-owned’ by the free artist who has a much greater ability to circulate the work outside the prison. In this way the work should and does circulate outside of our exhibitions. In the last nine months an amazing animation developed with 11 incarcerated artists and a Chicago artist, Damon Locks, has been played in about 12 classrooms, in four exhibitions and online. So there are ways that free artists can forward the work of incarcerated artists because the work is collaborative in nature. (See animation below.)

If folks are willing to really listen, there are many things we can learn from engaging this work. On the one hand there are obvious things, such as learning about state control, consequences of violence, poverty, and racism. But we can also learn about the challenges of staying mentally alive, having community inside and developing resistance to the boredom and monotony of incarceration. These two things go hand in hand, of course. For me I’ve learned a lot about the small ways control and regulation can work to reproduce power and shape subjectivity. I’ve also learned the way people develop autonomy against the odds.

“Freedom/Time,” video, 2015. Directed by Damon Locks in collaboration with incarcerated artists in Stateville Maximum Security Prison

HS: You write in an essay you’ve co-written with Erica Meiners “…any program in prison, even those with good intentions, can serve to create a ‘surface’ of rehabilitation or correction, while obfuscating the functions and daily administration of control.”[3] Can you speak a little about how PNAP struggle against this recuperation by the state?

SR: This is difficult for a few reasons. First, the state has total control in the prison and we operate at their permission. They will use our efforts to say that they rehabilitate, correct, reform, and so on. They will also kick us out any time they want. They have, and will, punish us for things that they find undermine their sense of security, such as taking an artwork out of the prison that they found questionable. To work against this we make friends with people or groups that can advocate for us. This is an important function because we want a chorus of voices on the outside to advocate for and know what is happening to people in prison — family members should not be the only ones carrying that weight. But even with this, the compromises to real creative and scholarly engagement in the prison might one day overcome us. We’re not a service organization and it is important that to do more than just teach basic classes in a prison. As a group we have discussed this and are aware of these limitations. At a certain point if we can’t teach rigorous courses, if we cannot have outside exhibitions or other engagements, then we’d have to ask ourselves what the project is doing then and evaluate its worth.

But the state is not monolithic thing. There are internal struggles in any prison system and within state politics. There are, indeed, people who work for the prison who want to see projects like ours. There are people in state politics who also have family members in prison or have been to prison themselves (we aretalking about Illinois here!) and they too want to see changes in the system. We have to work in these spaces and try to shape them to create the world we want to live in that includes a just, creative and radical education.

[1] tammsyearten.mayfirst.org/

[2] For information on Chicago Torture Justice Memorials as well as the various cases related to the John Burge see chicagotorture.org.

[3] Mainers, Erica and Ross, Sarah, “‘And What Happens to You Concerns Us Here’: Imaginings for a (New) Prison Arts Movement” in Zorach, Rebecca (ed), Art Against the Law. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp 17-30.