Alan W. Moore is the author of Art Gangs: Protest and Counterculture in New York City (Autonomedia). His research, pdfs and online zines are at: House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence // I ☠☢

Many good questions asking for short responses. Just to open two lines of argument… How to generate more concise counter-power? I’d say what’s needed is less concision and more encyclopedic inclusion.

First, to histories: Duncombe & Lambert ask art critics to “help us” by writing about political art. Why should they? Their job is to cover the novel, the interesting and exciting, the defining creative events. It is not to support any cause. People may diss Claire Bishop, but her line of criticism needs to be addressed. D&L’s call revolves around political issues of solidarity and criticism (party lines) which are not natural to artistic discourse. My discontent with the dominant creative activist approach is its intense post-modern localism. By this I mean the discipline—and by now it is clear that it is one—is anchored to media studies, not art history.

Creative activism is tied to advanced media, publicity, advertising, and nouveau ballyhoo. (There are historical reasons for this—money and jobs have been available in these sectors.) The new discipline ignores the lessons of the avant-gardes which are indigenous to artistic practice. Now a flood of new information is becoming available to Anglophone audiences concerning avant-garde tactics and resistances in Eastern Europe and South America. Instead of reviewing and reclaiming this legacy, it is set aside. So finally you produce something already known only with different content. To really dislocate contemporary reality, to clear the way for thoughts and feelings of and for something new—this is the traditional job of the avant-garde.

Even so, it is easier to escape histories than habits. I mean, the way to build a movement is to include, not to exclude. The way to build a discipline and careers within institutions is precisely the opposite. You mention “outsiders” and “insiders.” I think of myself as both. Most of us have been both, in respect to one or another place or situation. These positionalities are highly determining. We all ceaselessly reinscribe, police, and maintain our positions. They both enable and disable our work. The need is to imagine ourselves out of them, to imaginatively inhabit the positions of others—and regularly to open the gates and let flow between.

The excessive dependence of this (may we call it a…?) movement of creative activism upon institutions is the guts of the problem. Institutions are about capturing, binding, and enclosing creative energies and selling them to consumers (students, audiences). Privileged institutional actors have total freedom of movement within most of the discursive arenas they set up. Outsiders are either invited in or excluded—left out. When you are excluded you wonder why? Shall we go now to that place, that subjective state of whining?

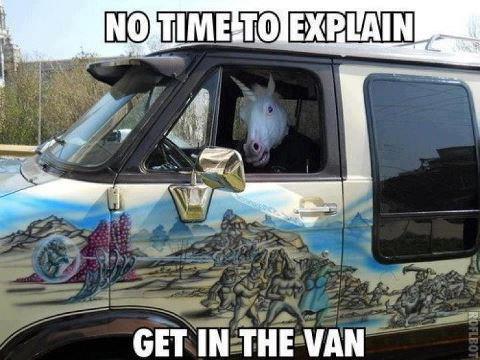

This image refers to uh, going along with people without getting any really good explanation.

The image is from a Facebook post by “Illuminator.”

Let’s not. Still, we can easily hear the strong silence around the operations of hierarchy. Opportunities—both within institutions and markets—have corrosive corollary effects among those who feel they should be part of something but are not included. I have seen these dynamics play out numerous times. In my years of work in collective movements and academies I have seen and felt a full typology of dissolutions.

Whether it is an artistic circle or movement which throws up one or a few successful individuals, or a social movement which produces one or a few spokespeople, the specter of super-competition—the social Darwin—stands behind every one of these formations, waiting for the opportunity to assert its “natural” operations. We shouldn’t be happy with that, even if we are among the winners after some round of the game.

Without an open clear attention to the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion, and a good deal more transparency and internal critique within collective formations, all of them will more quickly become historical objects rather than active growing movements. For the historian, this isn’t so bad. When movements are dead they are easier to study, just as when artists are dead they are easier to sell. This isn’t “our” logic, I hope. To continue organizing events in the approved style of hierarchical creation is, I think, to demonstrate a disinterest in the cause of radical democracy. I look to institutional actors to find ways of managing this better. Or if they can’t, to at least be honest about what they are doing.